Chapter 1: Scene 2

The first draft of scene 2. Another major character is introduced and we get a glimpse of how Joshua perceives his life in the village. Enjoy!

The drab, monotonous nature of the village had a funny way of draining the novel excitement out of his discovery on the beach. He was beginning to wonder if he’d imagined it all. The strangely dry, frigid air from before had given way to the uniform humidity of the Salvacian Peninsula. As he lugged the basket away from the beach, he had to reach into his pouch a few times for the crystal just to be sure of its existence, though the electric feeling of impending destiny was long gone. By the time he reached the market at the center of town, his good mood had evaporated in the summer heat like the sweat on his skin.

He moved mechanically through the market square, weaving like a shadow amid the growing mass of buyers and sellers. Tension marred his features as he grit his teeth and tried to ignore the tightness in his chest. He hated crowds. Because he wasn’t particularly tall, many towered over him, something he always associated with bars on a cage. It was much better to be on the outskirts, free and observant.

He reached his father’s tent stall at the western edge of the square and set the basket of fish on the counter.

“Good morning, my boy!” His father, Thomas, looked up from the ledger and greeted him with a smile that didn’t reach his eyes. They never did.

“Morning, father,” he mumbled, ducking under the shade of the tent and plopping down on the nearest crate.

“A fine catch today, I see,” Thomas remarked, peering into the basket of fresh minnow.

“Thank you, sir.” Now that he was sitting still, the boy became acutely aware of the dryness in his throat. He rummaged through his pouch in a futile attempt at finding his water flask, cursing inwardly when he came up empty.

As if on cue, Thomas cleared his throat expectantly. Feeling the impending lecture before it even started, he looked up at his father for the first time that day.

His father was short in stature but imposing in presence–even though they stood eye-to-eye these days, Thomas still had a way of making him feel small. He was stocky and powerfully built, with hairy forearms like tree trunks and fair skin that refused to tan despite a lifetime in the scorching sun, the evidence of his angling livelihood etched into the callouses on his hands and the seemingly permanent, angry-red patches of skin on his face that were always peeling. There was no hint of joviality behind his serious green eyes–not anymore. His dark hair framed his face and a thick, salt-and-pepper beard hid any emotion that threatened to betray his stoic demeanor. He was leaning against the counter with a dreadfully familiar water flask in his hand.

“Joshua, how many times do I have to tell you to bring your water with you?” Thomas began, tossing the flask over toward him. “You’re going to have a heat stroke one day if you aren’t careful. It wouldn’t be a big deal if you fished the southern shores with the other anglers. The fishing is more consistent there anyways.”

Joshua sighed inwardly and reluctantly uncorked the flask. He had half a mind to dump the water out of spite.

“And furthermore,” Thomas continued, pointing at Joshua’s bare feet, “You’re lucky you haven’t cut your feet open walking around the village like that! It’s not like you don’t have sandals…”

The recycled lecture continued, but Joshua had tuned it out. He preferred the world of dreams, whereas Thomas anchored himself to the salty reality of fishing hooks and transactions. With each day the divergence of their paths seemed to widen the expanse between him and his only parent. At nineteen, he was expected to pick up the family trade with enthusiasm. Joshua couldn’t imagine anything more hellish. He clutched in his pouch for the crystal once more, hoping for a burst of novelty, the faint promise of something more. It was strangely cold to the touch.

To his relief, a third voice announced itself, forcing Thomas to pause his scolding.

“Mornin’, Thomas!” Spouted the villager, blissfully unaware of the tension that hung in the air. “Good lookin’ catch today, eh? I’ll take a half dozen. Usual price?”

Thomas huffed, fixing Joshua with a stare that promised a rehashing of the same tired "discussion", before turning around to attend to the customer.

Joshua ran a hand through his hair–dark like his father’s. It was reaching an irritating length, the locks consistently falling into his eyes. Grateful to have the attention away from him, he took a few gulps of water and scanned the square.

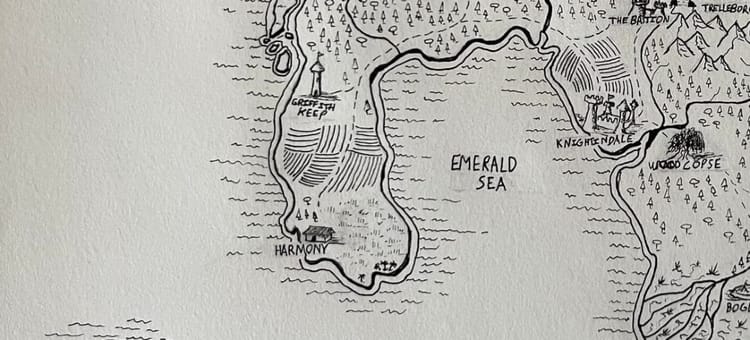

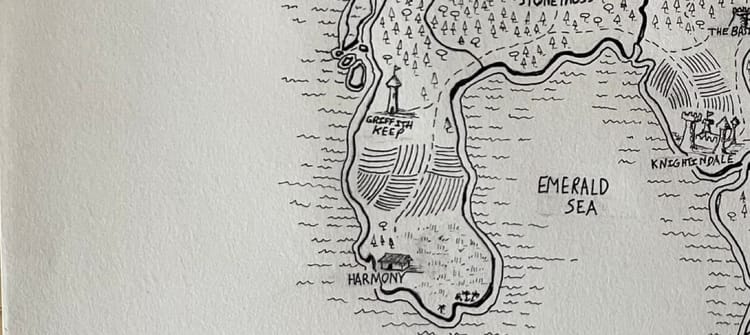

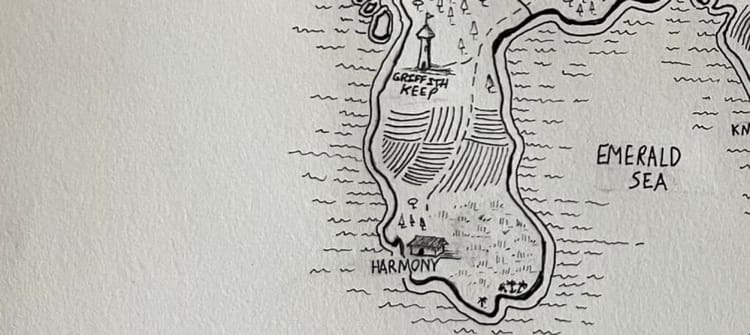

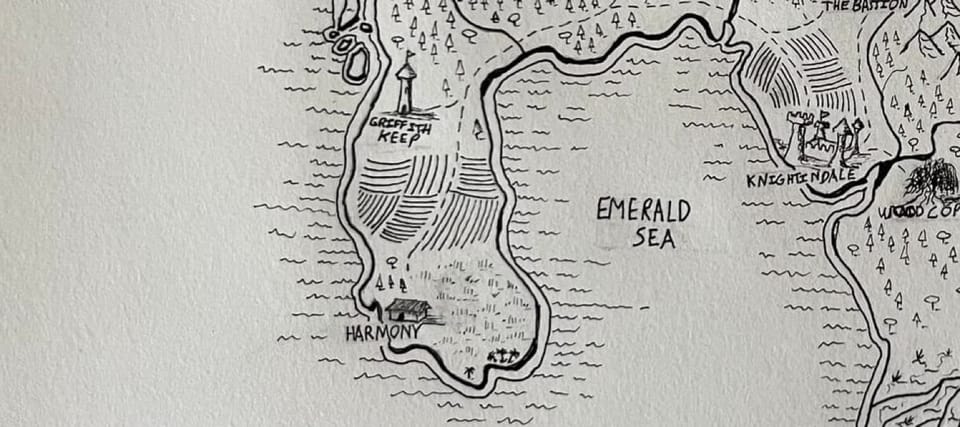

The market was far from luxurious, the unpaved ground so frequently trampled that not even a patch of weeds could grow. Lining the perimeter were rows of stalls constructed of old, splintered wood and tattered canvas for meager shade. It was midday, and the place was buzzing with trade, a kind of chaos that resembled a collection of simple patterns if one looked closely enough. Men and women exchanged food, clothing, and handmade products. He spotted Mrs. Maple, the best weaver in all of Harmony, haggling with a frugal customer over the price of a basket. In strode a hunter through the northern entrance, a bow slung over his shoulder and a number of squirrels hanging from his belt.

Joshua chuckled to himself as he caught a flash of commotion on the other side of the market: A rogue chicken was darting through the crowd, squawking gleefully, its exasperated owner in clumsy pursuit. Elsewhere, a pair of boys no older than ten were dueling with sticks, miles away in their own world of knighthood and bravery. Some Salvacian guards clad in chainmail and purple tunics leaned against their spears, looking on in amusement at the little would-be knights. In the center of the square was a well of weathered stone. Planted next to the well was a rickety pole that flew the Salvacian Standard, a purple flag adorned with a white owl, its colors robbed of their vibrancy from many years of enduring the sun.

A heavy feeling settled in his heart. Such was the fate of all things in this place, he thought, slowly crumbling away in the heat, as impersonal and relentless as the time which crept by in its equally unstoppable nature. What a fate it was to fall victim to the prison of routine, to fill a basket with fish every morning and trade it for some bread or clothing every day, waking and dying in the exact same spot as ones ancestors, all in the name of safety and predictability. According to his father, these were virtues.

“Boo!” Exclaimed a melodic voice so close to his ear that he nearly leapt off the crate.

He whipped around, his frigid annoyance melting into warm affection as he found himself looking into the soft brown eyes of the auburn-haired girl who occupied so many of his dreams.

Ethan Mark